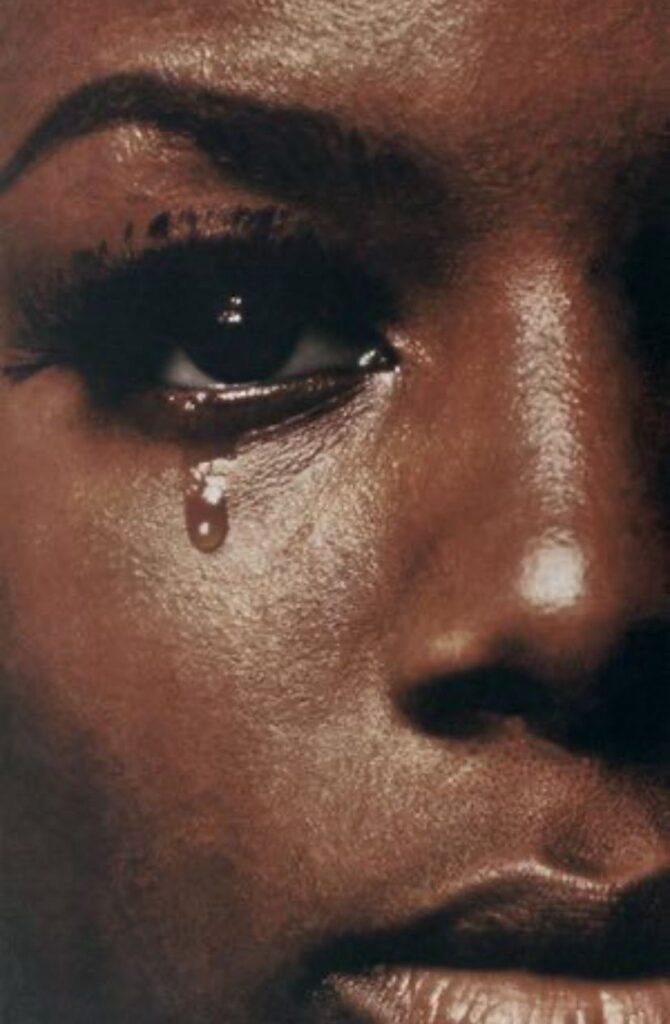

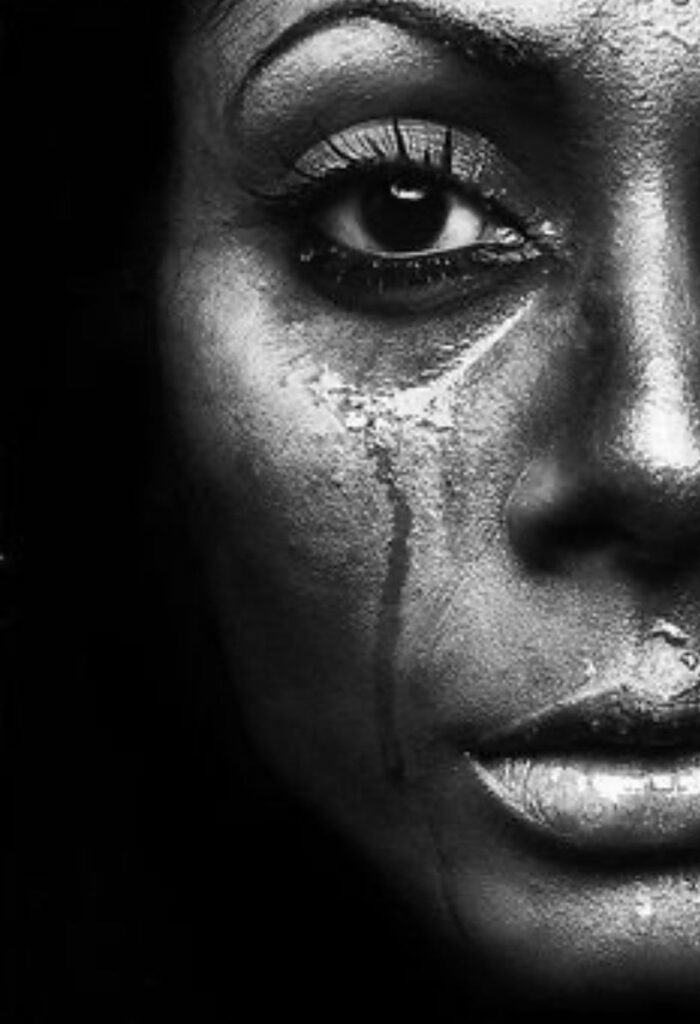

Dominican Republic Strips Thousands Of Black Residents Of Citizenship, May Now Expel Them

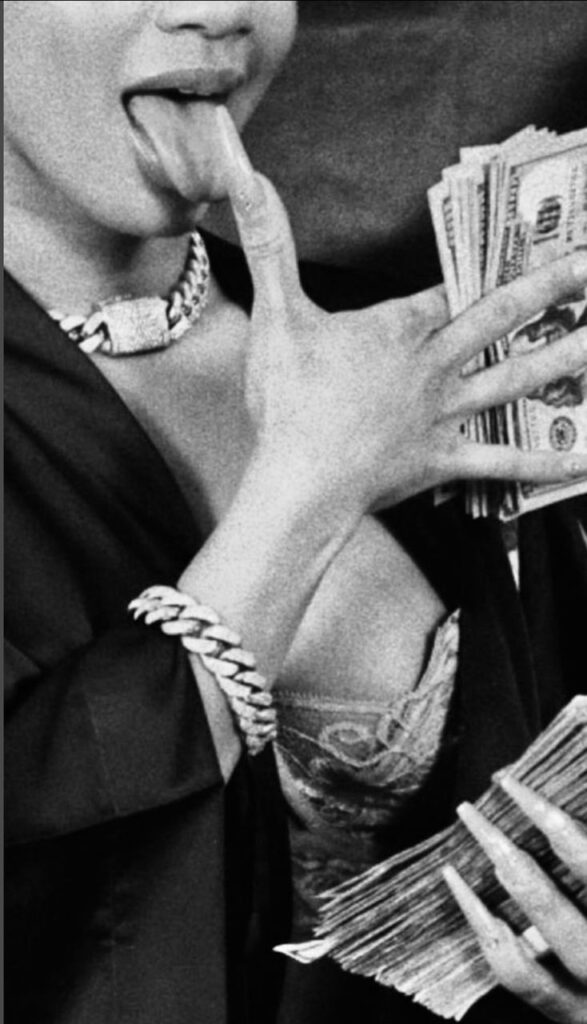

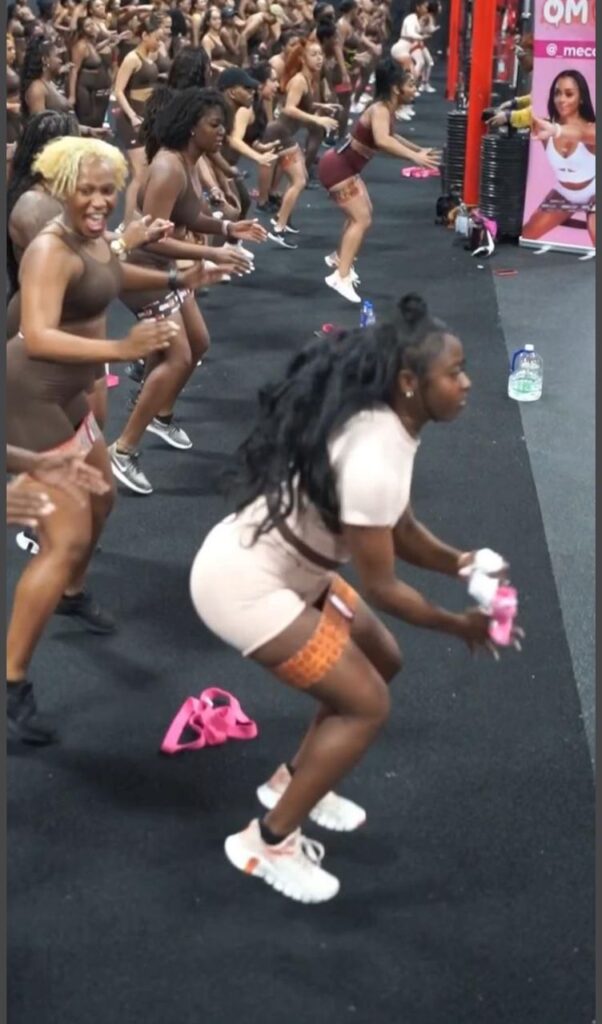

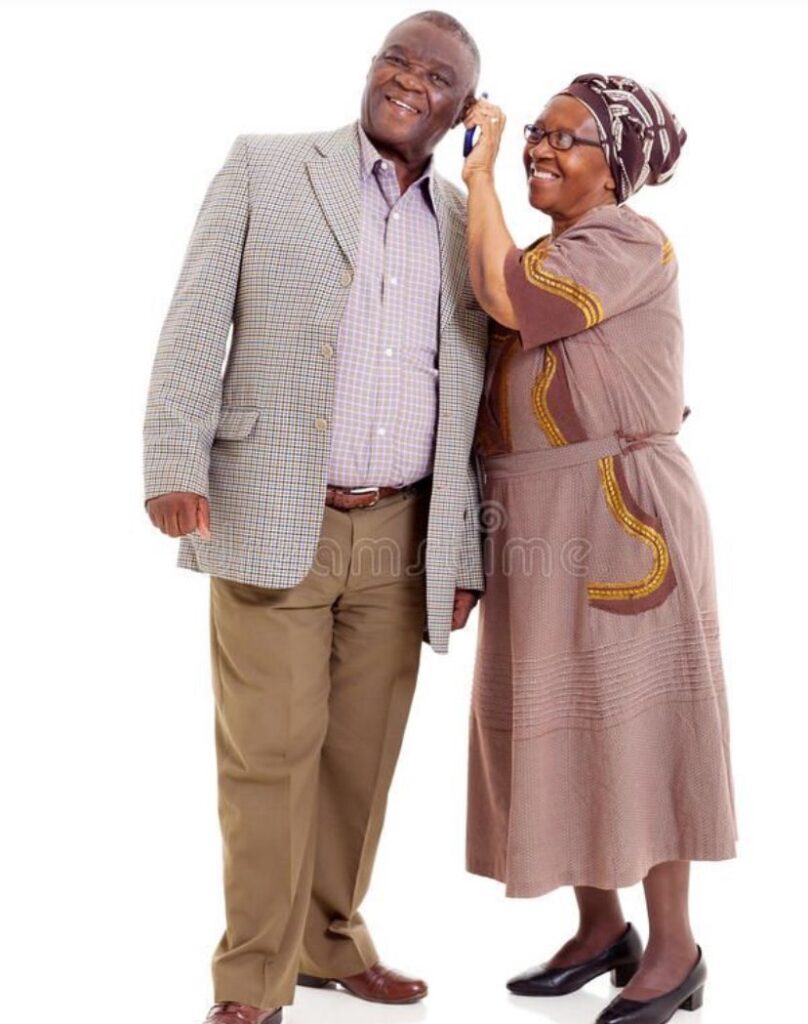

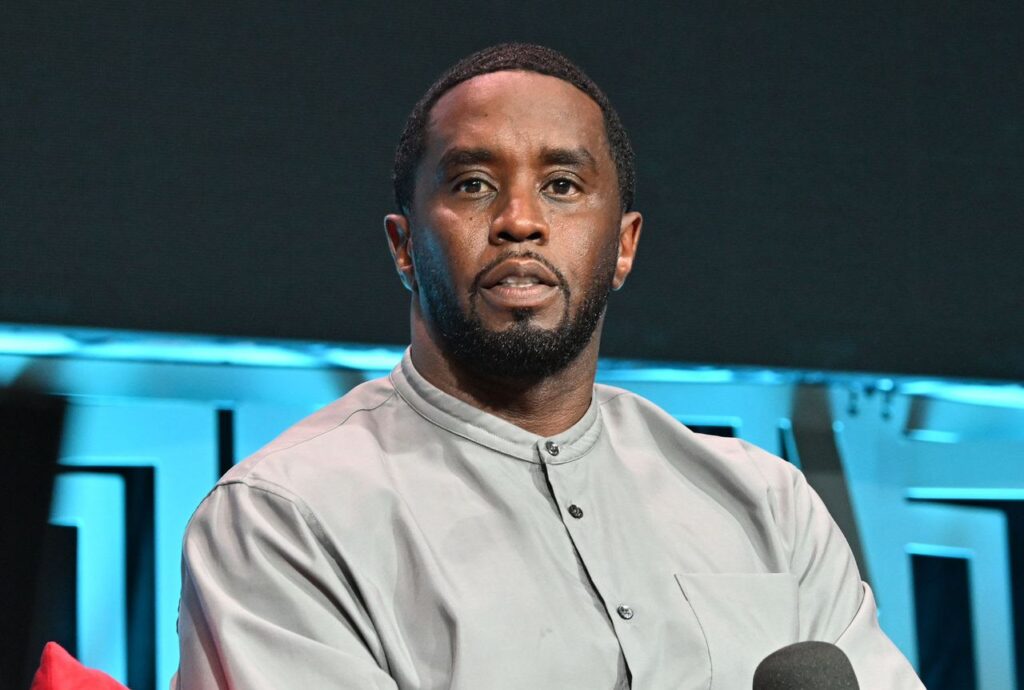

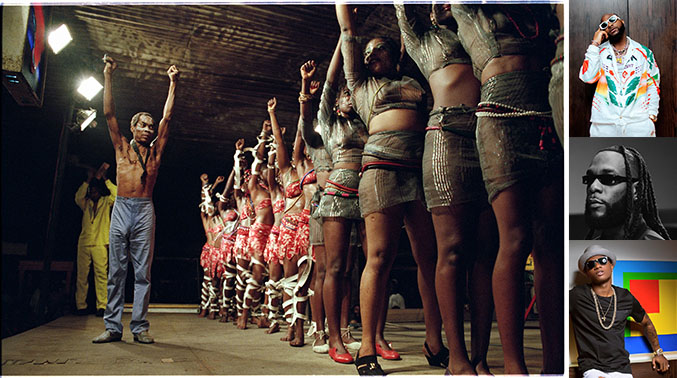

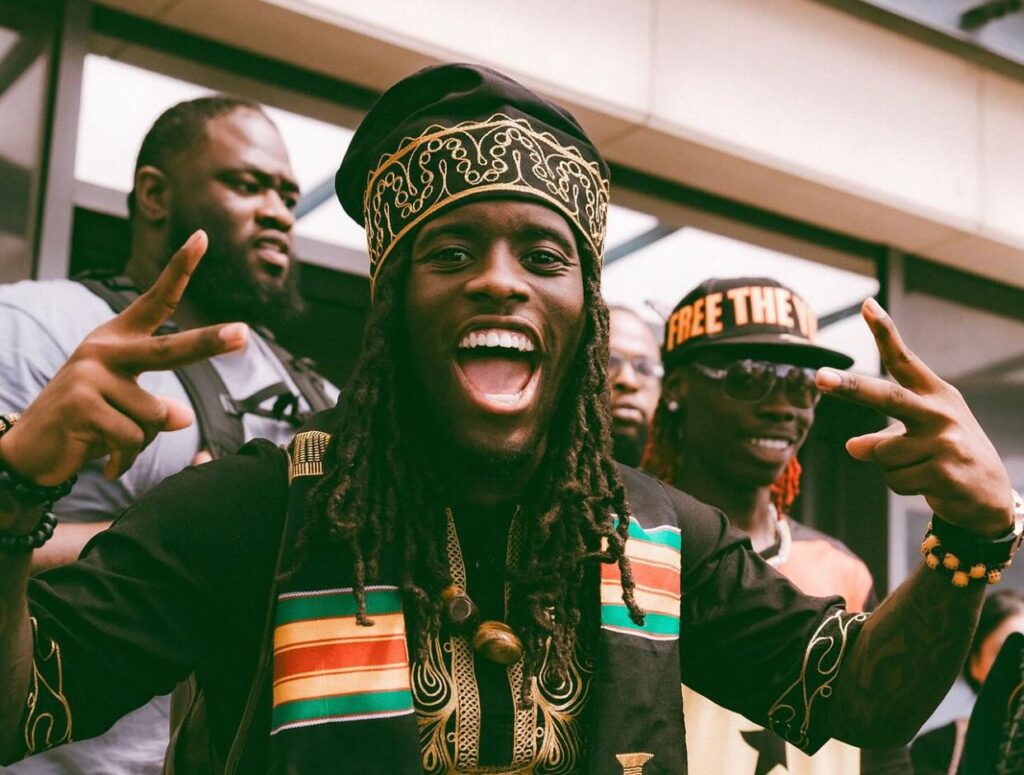

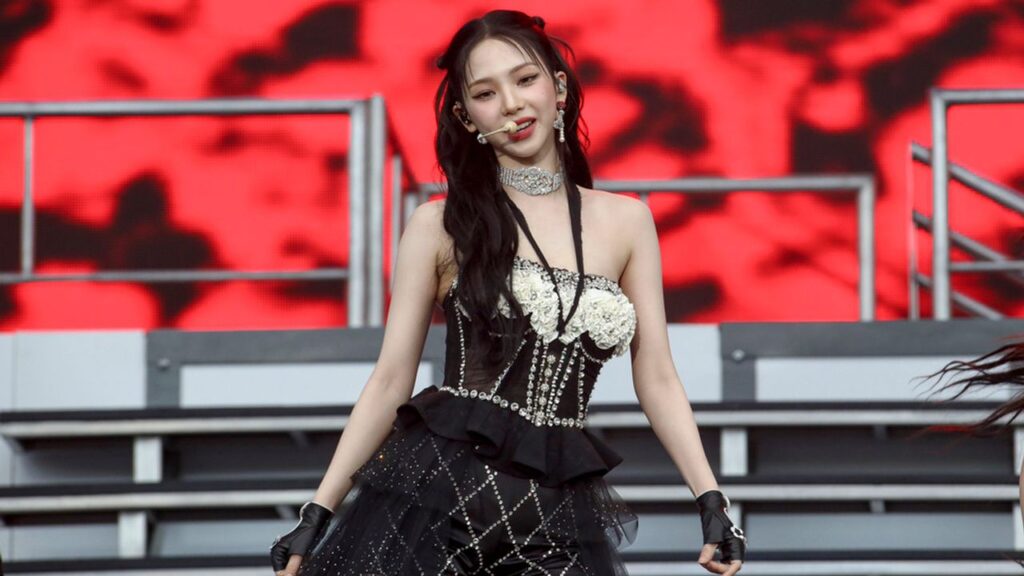

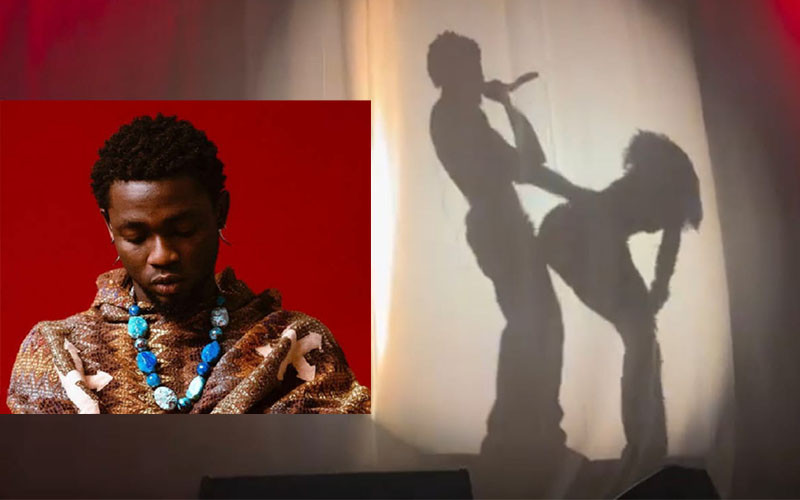

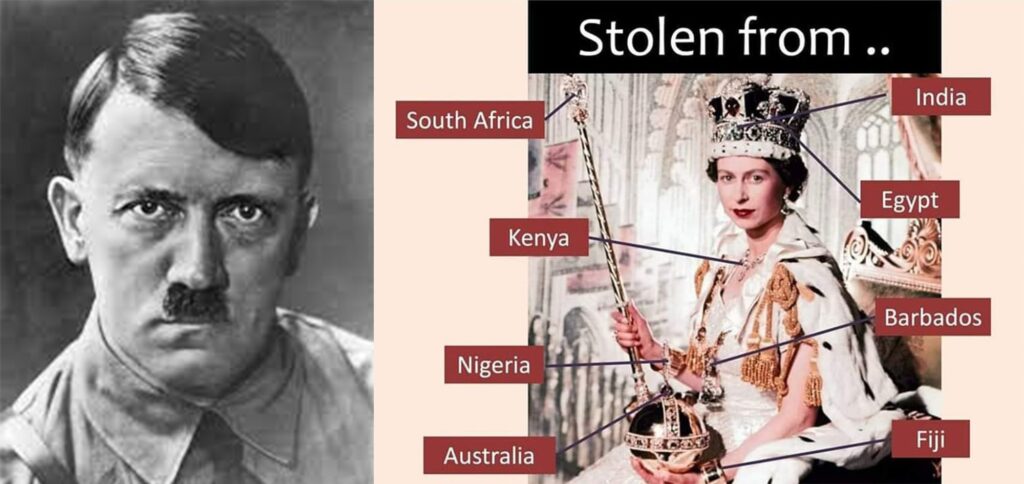

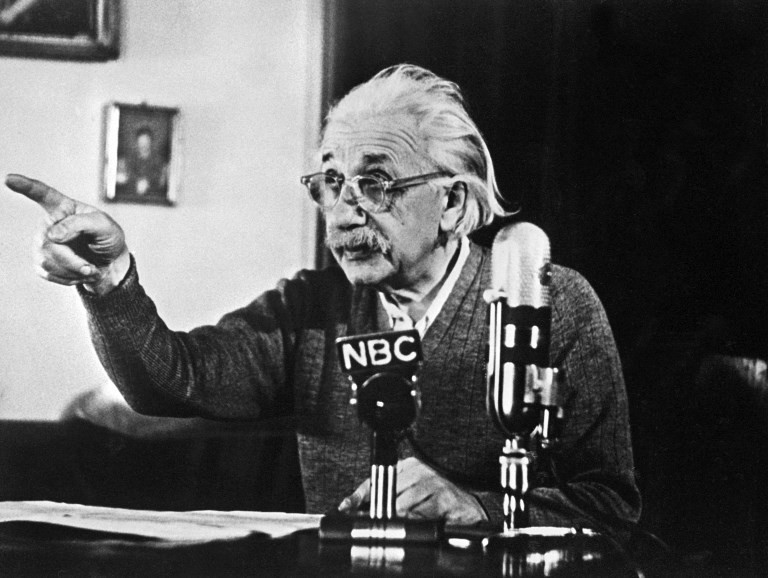

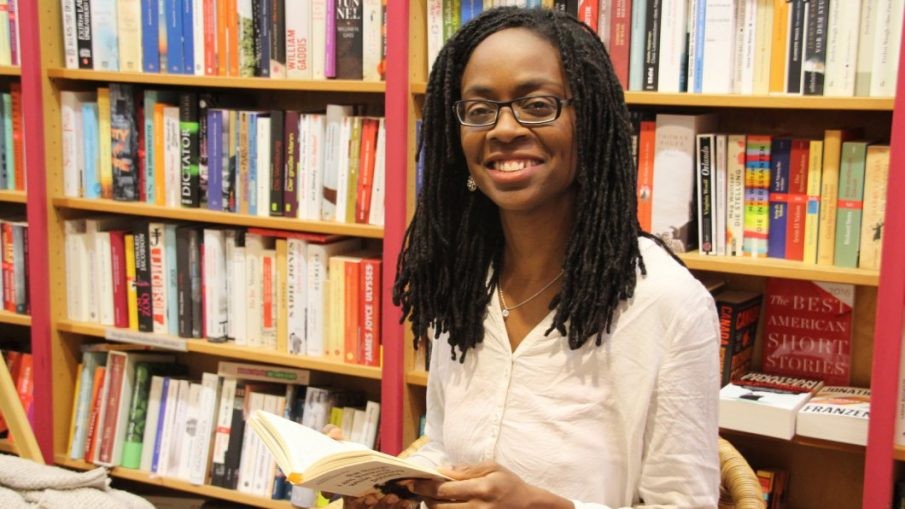

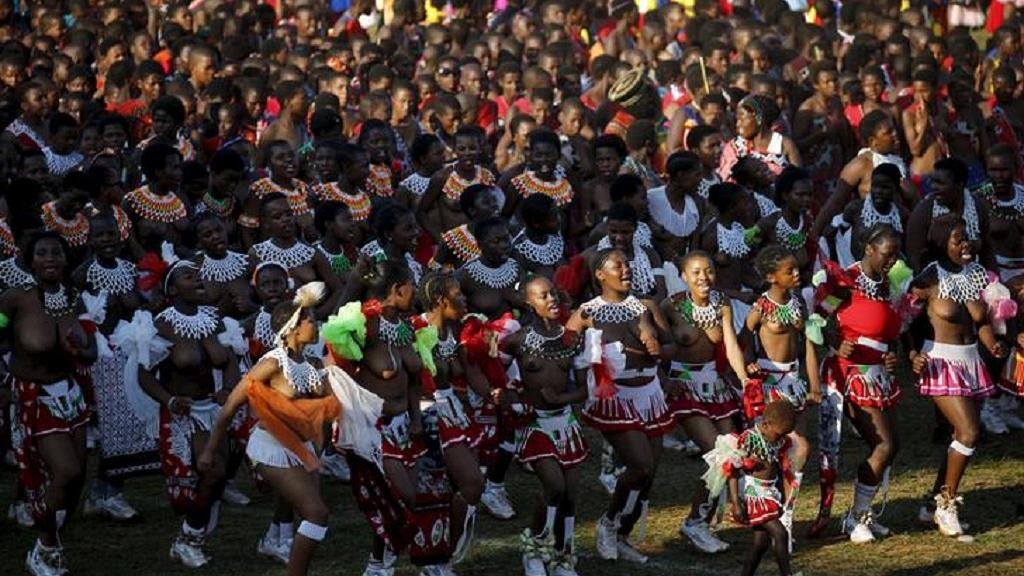

Soldiers address Haitians and Haitian-Dominicans without birth certificates as they try to register under the country’s new foreign migrant law. ( ERIKA SANTELICES/AFP/Getty Images)

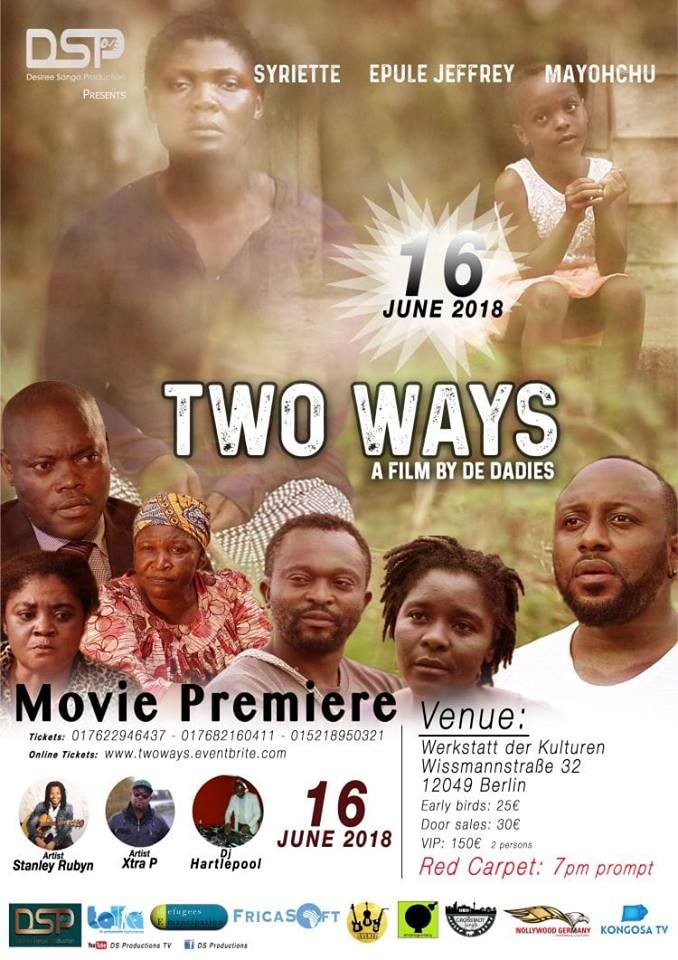

In 2013, the constitutional court of the Dominican Republic announced a decision that stripped an estimated 210,000 people — about 2 percent of the island nation’s population — of their citizenship overnight.

The Dominican Republic is a Caribbean nation that occupies roughly two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola. The other half belongs to Haiti, and the two countries are divided by language, history, and race. That division has often been toughest on Dominicans who are of Haitian descent, which is the group of people who lost their citizenship in the ruling.

The government later softened the decision to allow people with birth certificates to “validate” their citizenship, and those without them to register as foreign migrants, the deadline for which was last night at midnight. But because the Dominican government has for decades systematically refused to grant birth certificates to people of Haitian descent, thousands were never able to obtain validation.

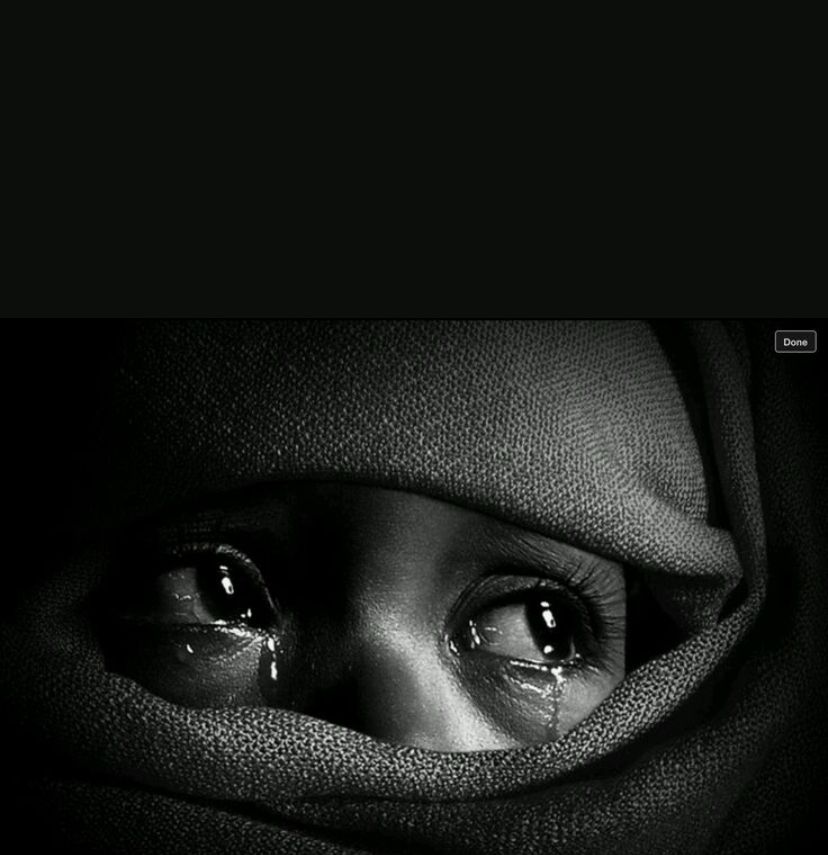

That means there are now fears of what human rights advocates have warned would be an act of ethnic cleansing: that people of Haitian descent who cannot prove their right to stay will be rounded up and forced to “return” to Haiti — a country where many of them have never lived.

Although the country’s president and foreign minister have promised there will be no mass roundups, the government has announced that it is readying buses and detention centers to gather and deport people of Haitian descent, and has placed 2,000 troops on standby to support the process.

The Dominican government has cloaked this all in the language of immigration and border control, but the truth is much uglier. This is part of a much longer and more sinister story.

The Dominican Republic’s long history of anti-Haitian violence

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3803206/GettyImages-477477070.0.jpg)

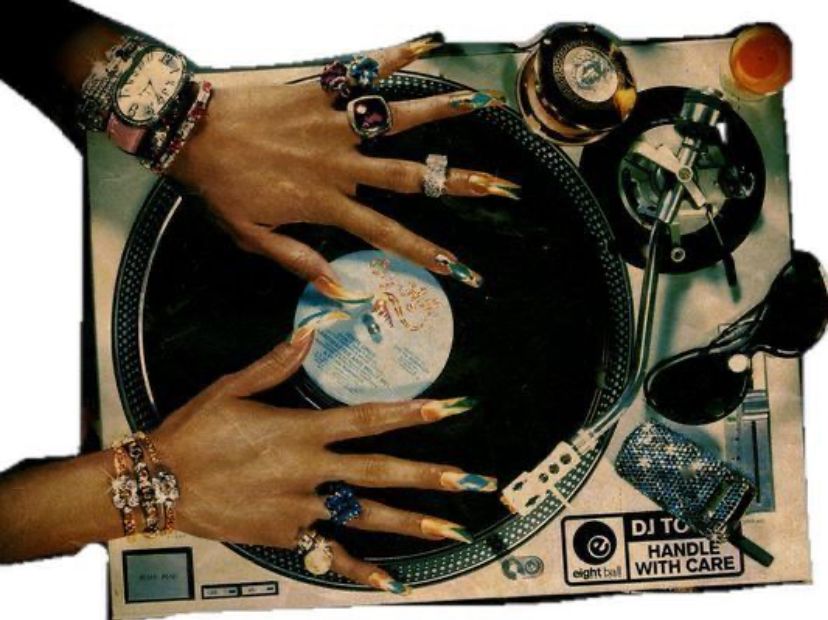

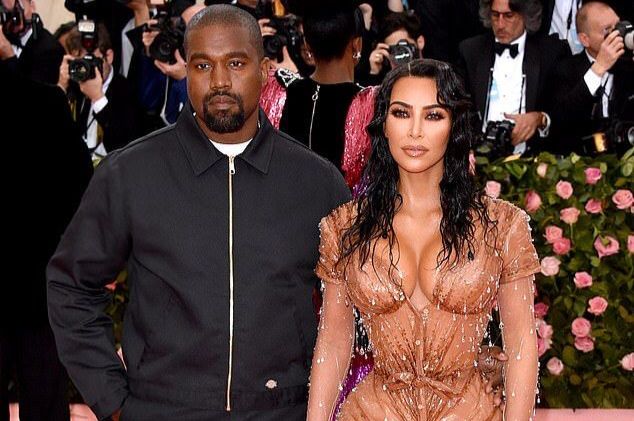

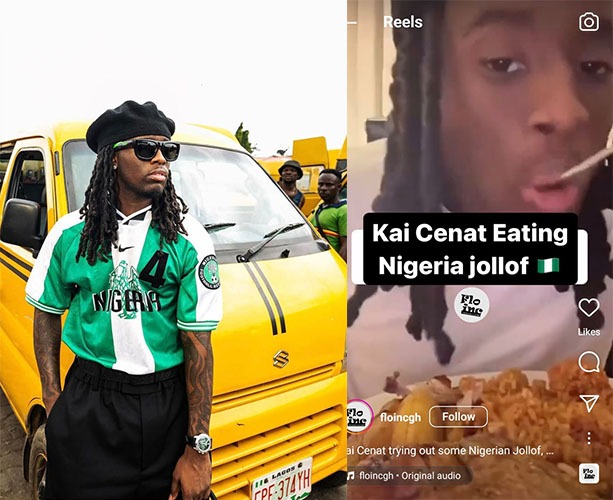

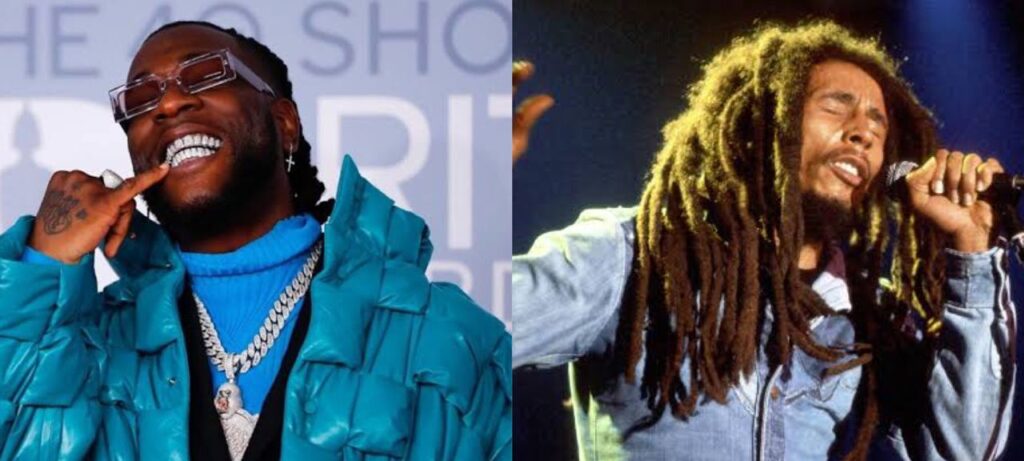

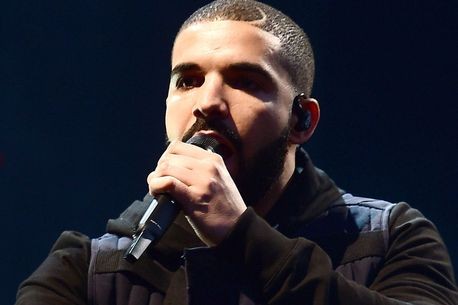

Thousands waited for days in Santo Domingo for a chance to avoid expulsion by registering as foreign migrants. (ERIKA SANTELICES/AFP/Getty Images)

In 1937, Dominican government forces launched a bloody campaign of ethnic cleansing against people of Haitian descent that left thousands, or perhaps even tens of thousands, dead. It became known as the perejil or “parsley” massacre. Supposedly, troops who’d found a suspected Haitian would hold up a sprig of parsley and ask them to name it. Those who could not pronounce its Spanish name — perejil — with a properly rolled “r” were presumed to be Haitian Creole speakers, not “true” Dominicans, and killed.

This was the most infamous incident of anti-Haitian violence in the Dominican Republic, but it was far from the only one. The ongoing crisis affecting Haitian-Dominicans is considered so scandalous because it is widely seen, with good reason, as just another episode in this history of discrimination. And it is considered so dangerous because of what the Dominican government has proven itself capable of in the past.

There have been numerous other incidents of violence and discrimination against the Haitian-Dominican community. A 2002 Human Rights Watch report documented mass expulsions of Haitians and Haitian-Dominicans in 1991, 1997, and 1999, and to a lesser degree in 2006.

During those episodes, soldiers rounded up thousands of people en masse on the basis of their “Haitian” appearance and forcibly transported them over the border into Haiti, regardless of whether they had Dominican citizenship or were legal residents of the country.

In 2005, the murder of a Dominican woman near the Haitian border triggered pogrom-like attacks on Haitian communities in the Dominican Republic, in which houses were burned and property destroyed, as well as the mass deportation of approximately 3,000 people. A few months later, a mob lynched four men of Haitian descent in Santo Domingo, gagging them and burning them alive. The following November, following allegations that two “black” men had killed a Dominican worker, mobs attacked the Haitian community in Guatapanal. According to the New York Times, the mob chanted, “Where there are two Haitians, kill one; where there are three Haitians, kill two. But always let one go so that he can run back to his country and tell them what happened.”

The legacy of “antihaitianismo”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3803192/GettyImages-477511946.0.jpg)

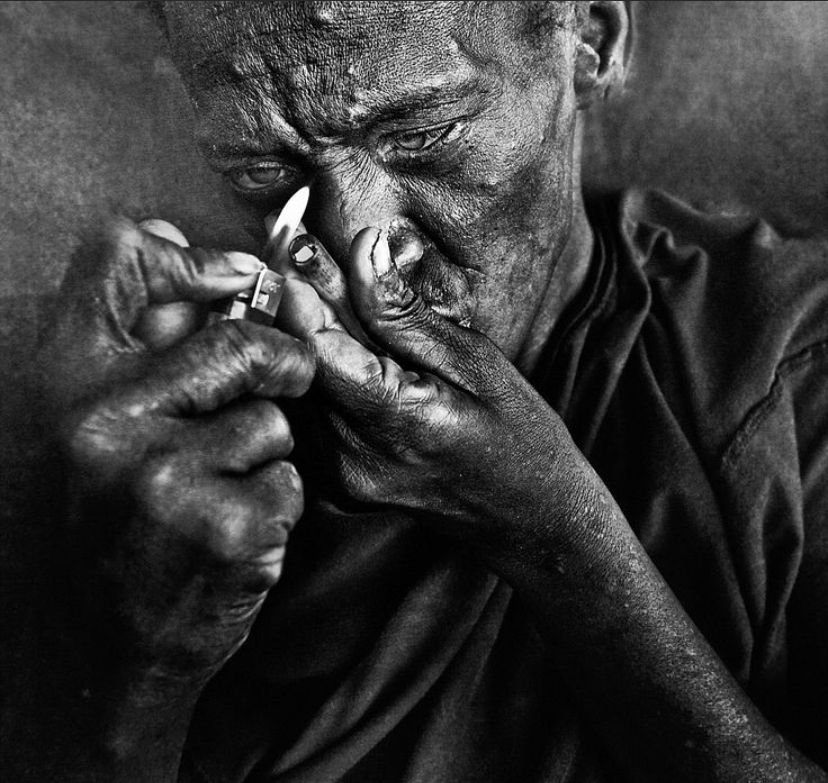

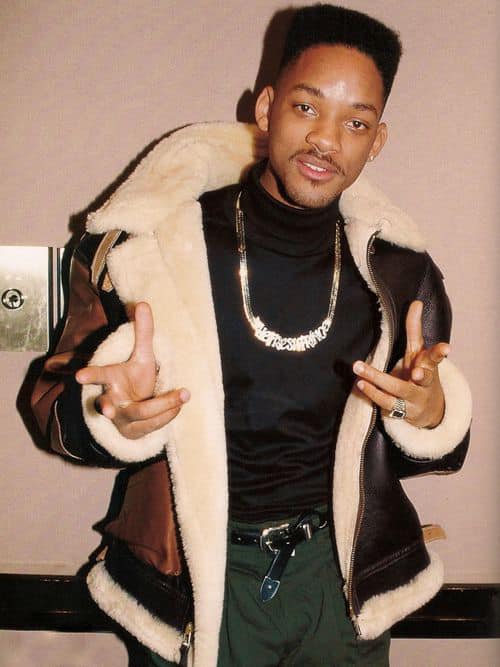

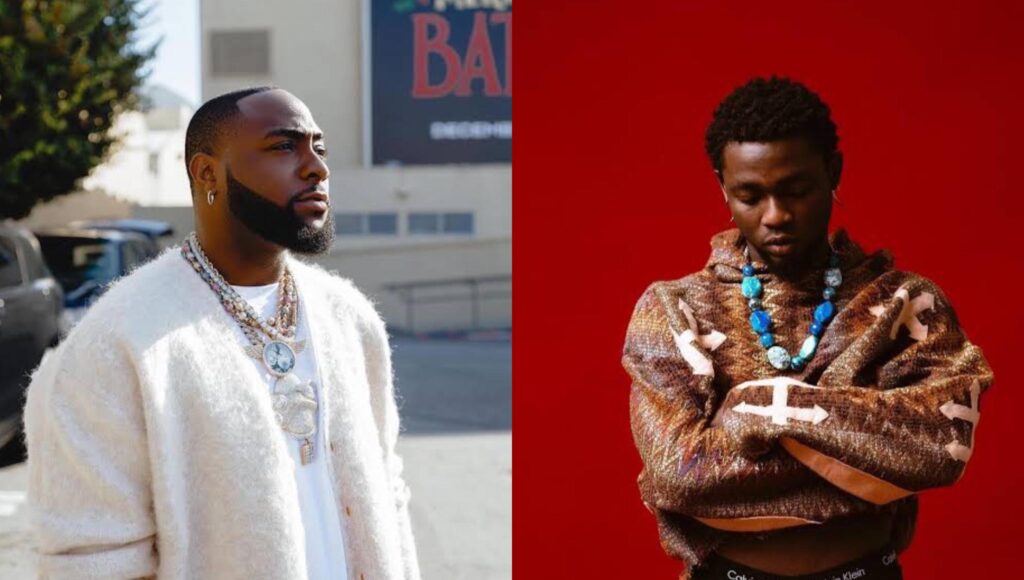

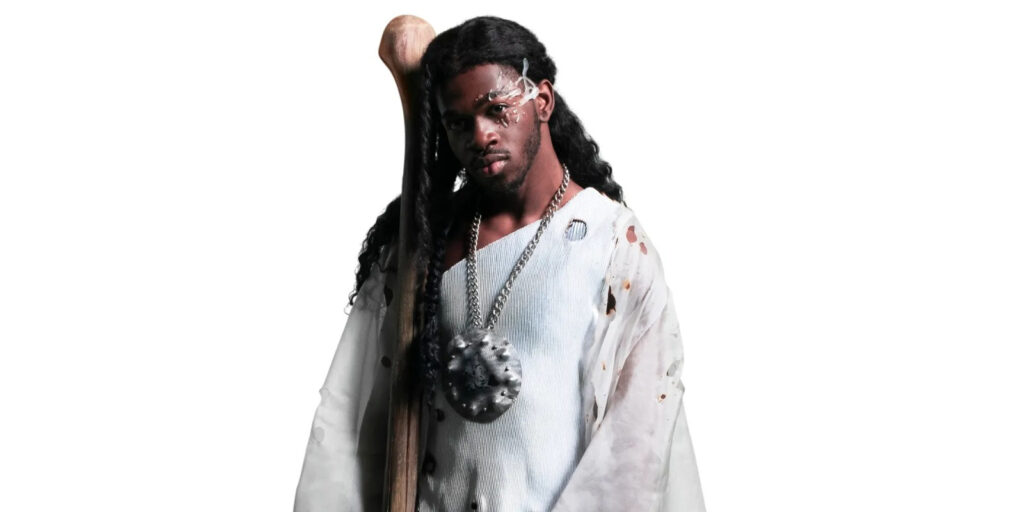

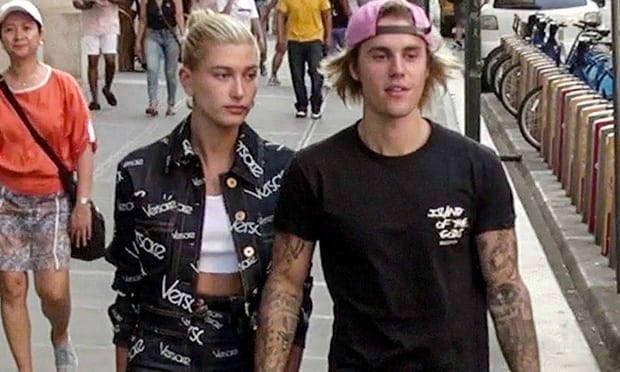

Haitian sugar-cane laborers march to the National Palace to protest the plan for foreigner registration. (ERIKA SANTELICES/AFP/Getty Images)

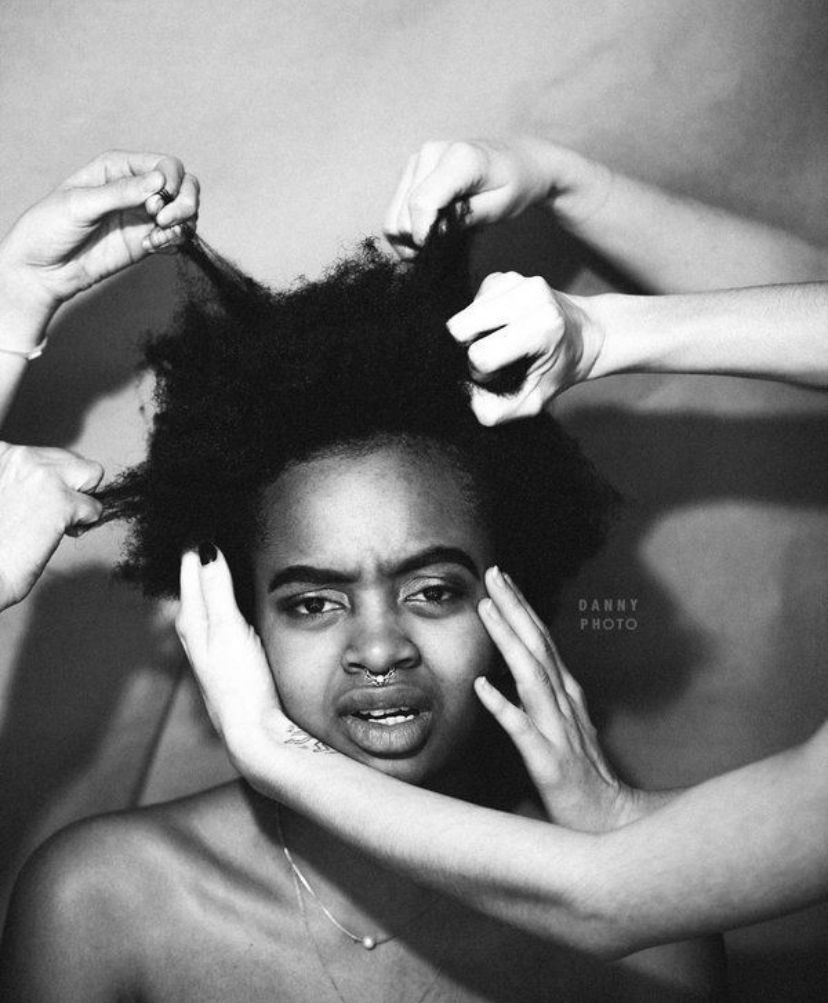

The earliest roots of “antihaitianismo” — racist, anti-Haitian discrimination in the Dominican Republic — go back to the colonial era. Spain and France had divided the island of Hispaniola between a Spanish colony, now the Dominican Republic, and a French colony, now Haiti. The countries’ racial makeup is also different: Haitians are predominantly black, the descendants of slaves who were brought to the colony to work on French sugar plantations, while Dominicans consider themselves Hispanic.

After independence, Dominican nationalists sought to “emphasize their racial and cultural distance from Haiti,” according to Human Rights Watch. This included efforts to “improve” their country by encouraging white immigration and imposing strict controls on nonwhite migrants.

When military dictator Rafael Trujillo took power in 1930, he portrayed himself as a “defender” of the country and its culture against the supposed Haitian threat, and promoted racist stereotypes of Haitians as lazy and untrustworthy. His forces were responsible for the 1937 perejil massacre.

Trujillo’s legacy remains: a durable set of dangerous, racist stereotypes that has left Haitians in the Dominican Republic vulnerable to violence and discrimination ever since.

There is a real tension, though, in how the Dominican Republic has approached its Haitian population. The country, particularly its sugar industry, has long relied on inexpensive Haitian labor. Haiti, as the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, has lots of citizens who need work. In the 1950s, the Haitian and Dominican governments entered into a series of bilateral agreements to ensure a steady supply of Haitian migrant labor for the Dominican cane fields.

These migrants were often essentially enslaved, sold by Haitian gangs or politicians to Dominican bosses and forced to work on the plantations for little or no money. When the annual sugar harvest ended, the workers were often expelled en masse — creating the conditions for a cycle whose legacy we see in today’s crisis.

The result is the situation today: economic migration has left the Dominican Republic with a large population of Haitian-Dominicans, but the long history of discrimination and racism against them has left their communities socially and legally marginalized.

How the current crisis began: by stripping Haitian-Dominicans of citizenship

The Dominican Republic, for some time, was like the United States and many other Western hemisphere countries: if you are born on native soil, you are a citizen. In 2010, however, the country amended its constitution to change that rule. Going forward, only children whose parents were citizens would automatically received citizenship themselves. That was not necessarily a disaster in and of itself: many countries around the world follow a similar rule. But then came a court decision that made the constitutional change much, much more damaging.

Today’s crisis began with a woman named Juliana Deguis-Pierre, who was born in the Dominican Republic to Haitian migrant workers. When she applied for an identity card at 24, government officials refused to issue one, insisting she was not really a citizen and her Dominican birth certificate had been issued “in error.” She sued, and got all the way to the constitutional court, but her case ended in disaster.

A new rule, the court announced, would apply: anyone born in the country after 1929 to parents who were “in transit” was no longer a citizen. That included the children of Haitian migrant workers — a group that included over 200,000 people, including Deguis-Pierre. The court instructed the government to open the records of the birth registry and revoke the citizenship of anyone unable to meet the new criteria.

Following an international outcry, the government of the Dominican Republic passed new legislation allowing people with birth certificates to apply to regain their citizenship. It was not the progress it seemed. Government authorities have for years systematically denied birth certificates to people of Haitian descent, even if they could prove their native birth. As a result, even Haitian-Dominicans whose families had been in the country for decades may lack birth certificates.

Those Haitian-Dominicans can only register as “foreigners.” That lets them stay and pursue naturalization, but in the meantime it leaves them officially stateless — citizens of no country at all. That’s not merely an administrative matter: citizenship is the foundation of all legal and political rights, which means that stateless people are often left with no legal access to work, education, basic services, or even minimal legal protections. And the few registration centers have been overwhelmed, forcing applicants to stand in days-long lines to submit their paperwork.

In the days leading up to the deadline, many of those people have lined up in the streets at local government offices, desperately seeking the requisite paperwork to stay, if not as a citizen then as a “foreigner.” But some will not be able to submit their documents in time, and others have refused to register because doing so would require them to accept immigrant status, rather than the citizenship that was their birthright. According to Dominican law, those people have just become illegal aliens in the country that’s been their home all their lives.

Source: www.vox.com

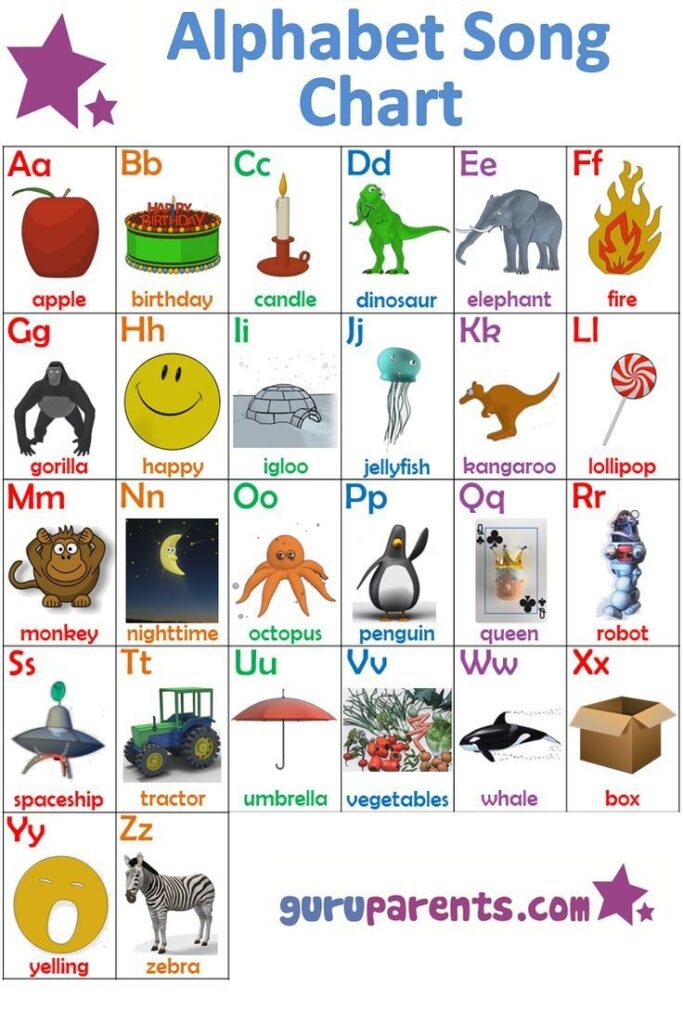

English

English